Manifold.markets is a prediction marketplace that allows you to bet on anything (for play money). Sign up with Google, ask your question, wait for the Wisdom of Crowds to tell you the answer. Alternatively, if you have expert knowledge about a particular question, you can bet on the answer and make (play) $$$ if you’re right.

The promise of prediction markets is that through a combination of ‘wisdom of the crowds’ (i.e. everyone’s biases cancelling each other out) and ‘expert knowledge’ (including insiders who already know the answer and want to get rich quick), they’ll trend to an accurate price. The sum of human knowledge is thus increased, we can accurately predict the outcomes of our decisions, make better decisions, and immanetize the eschaton.

How accurate prediction markets really are, and how well they perform against experts alone, is very much an open question (this section of a Scott Alexander piece summarizes the current discourse pretty fairly).

Let’s look at this slightly differently.

The foundational principle of the prediction market is that participants have skin in the game - they are betting something of ‘value’ (money/reputation/play-money) and thus are incentivized to contribute honestly and competently. So, let’s take the same approach when judging their accuracy: what would happen if we simply bet with each market as it closed, effectively saying ‘I don’t know anything about this particular isuse, but I’m willing to bet you’re right’.

To find out, I used the Manifold API to download all 4,628 markets that have ever been created and loaded them up in PowerBI. The simplest market type on Manifold is a ‘Binary’ market, where you can bet either YES or NO on a given question. The ‘probability’ of the market, which determines the payout you get when the question is answered, updates accordingly:

This market currently thinks there’s an 81% chance that Celsius will crash this year. If you think 81% is too low - that it’s basically certain to crash - then go and buy some YES. When the market resolves, every share of YES will be resolved to M$1 (1 ‘mana’, Manifol’s play currency), so you’ll make M$0.19, minus fees.

Of the 4,628 markets created so far, 3,090 are binary markets (the other types are numeric, which is bugged beyond all reasoning at the time of writing, and ‘free response’, eg “What’s my favourite flavour of crisp?”). Of those 3,090, only 1,677 have actually been resolved either YES or NO; the rest are either still open or were cancelled.

We can then look at the probability of the markets at the time they closed to see close to reality they were:

This lines up pretty well with the ‘official’ stats produced by Manifold’s staff, which you can find here. The relevant graph is about half-way down the page:

On the face of it, that seems pretty good! I doubt I’m right 80% of the time about… anything, really. It means that, in theory, we could wait until a second before the market closes, bet with the majority, and make some free money.

But would that work? Averages can be tricksy things; to my idiot brain it seems possible that some Simpson’s paradox could occur that might mean we pick up pennies in front of a steamroller on lots of markets and then get run over on the 20%. Fortunately, we have the data! We can test this.

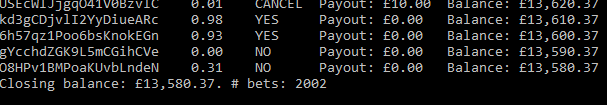

Using the market data, I ran a super-simple simulation in which I bet with the market (i.e. if probability > 0.5, buy YES, otherwise buy NO, and stay out of markets that are completely undecided and on 0.5 exactly). To be as generous as possible (and also because it’s difficult to calculate and I’m lazy and stupid) I didn’t include fees.

With a starting pool of $M100, and a standard bet size of $M10, the results were moderate but positive:

2,002 bets to triple our money; it’s not a particularly strong indicator of belief in the quality of the markets, but it’s not terrible either. Part of the problem here is of course that following the herd means our downside is always a total loss (we bet YES, market resolves NO, and we lose the entire bet), but our upside is capped at a 99% gain and will normally be much less than that (because, as per the graph above, the closing probability of a market is normally ~80% of reality). This means that we have to win a very high proportion of our markets, because a single loss can eat the profits from multiple wins.

Perhaps we can improve our odds by excluding some of the sillier markets - the personal or ‘fun’ markets like ‘Will I get a girlfriend by X’, which will have, at most, a handful of ‘experts’ (i.e. people very close to the market) contributing, and so I would expect to be wrong more often than usual.

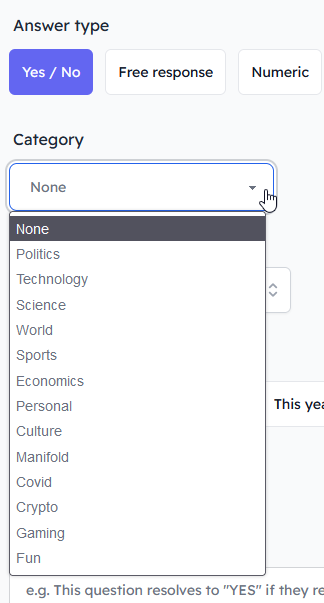

When you create a market on Manifold, you can select a category:

These appear to be represented as ‘Tags’ in the API, so it should be simple enough to do some filtering. Let’s see what tags have been created, and then remove the silly ones…

Oh.

I assume that at some point in the past the category system was slightly more permissive than it is currently. Shout out to “GurbangulyBerdymukhamedovGloriousLeaderOfAllTurkmenAndTotallyDemocraticPresidentForLife”; I’m sure that was a highly useful category that was widely used.

Ok, well, let’s do the best we can with what we have, and start by ignoring any markets that have a ‘personal’ tag:

An improvement, but not a massive one. Cutting down the markets further to only include those the ‘official’ list results in a higher profit and a much smaller number of bets:

This isn’t terrible. But it’s still reliant on betting correctly too many times for my liking. From the excellent Peter Brandt:

Years ago, […] I conducted an unscientific survey among about a dozen or so consistently profitable professional traders. Over the years I have asked the same question to trading novices. The question I asked was:

You have your choice—two different trading approaches. Both performed equally in recent years; one was profitable 30 percent of the time, and the other was profitable 70 percent of the time. Which approach would you be more apt to adopt?

Professional traders choose the 30 percent right approach by a two-to-one margin. Novice traders overwhelmingly choose the 70 percent approach. Why the difference?

Professional traders recognize something that the novices may not comprehend. There is no margin of error in the approach that needs to be right 70 of the time in order ot produce its expected results. What happens if the 70 percent approach has a bad year (50/50 ratio of losers to winners)?

— Diary of a Professional Commodity Trader, Peter L. Brandt.

The obvious implication of this for our case is that we should not adopt a strategy in which we have to make a very large number of small successful bets to make a profit. Instead, we should look for a strategy in which we can be wrong almost all the time, and profit nevertheless.

So what happens if we bet against the markets?

Woof. But that seems a bit too good to be true. How’s that happened?

It looks as though this particular market had a closing resolution very close to 0. In fact, when we look at the actual trade record, the final probability was 0.000000298733 - which meant that our M$10 bet bought us 33 million ‘YES’ shares.

That’s a pretty good example of Taleb’s barbell strategy in action - we only had to get lucky once to break the bank - but I suspect that Manifold might not have actually honoured that market had someone bet correctly. So let’s run this again, excluding markets where the probability is < 0.001 or > 0.999. This is ‘unfairly’ restricting our possible profits but I think it’s more realistic than the alternative:

That’s more like it. So what’s the catch?

In short, you run the risk of bleeding to death long before your strategy pays off - and that’s a problem that’s likely to get worse if Manifold’s markets get more accurate and less prone to obvious silliness and manipulation. Our total profit at the end of the run was M$13k, but our total income was M$29k. Of this, almost a full M$18k, 64% of our winnings, came from six markets, which paid out M$1-5k:

https://manifold.markets/ConnorMcCormick/will-manifold-markets-suffer-from-s

https://manifold.markets/kazoo/do-i-feel-alive-today-e74f9b3ae69b

https://manifold.markets/DAL59/will-the-worth-the-candle-art-in-rp

https://manifold.markets/VivekHebbar/will-this-market-have-an-even-numbe

https://manifold.markets/Predictor/will-the-tesla-tsla-stock-price-clo-695945fb182f

https://manifold.markets/AngolaMaldives/this-market-is-a-grift-exploiting-l

At least three of these are, to put it nicely, scam markets, of a kind that don’t seem to be made much more since Manifold stopped offering three markets. The others are ‘legit’, in sense that they seem to seriously attempt to predict some actual events, but they all feel slightly dodgy to me because of the way in which their rates bounced around so sharply during the life of the market, such as in this example:

Ultimately, there’s only one way to know whether this will work for sure, and that’s to try it. I’ll buy $M1,000, write a quick bot to lay every market at close, and let you know when I’ve bought my (play) Lambo.

Hey, I've noticed that you were betting against the market everywhere and so I went to your substack to see what you had to say and I wasn't disappointed! This is very interesting :) Also, it seems as though it's working pretty well so far!